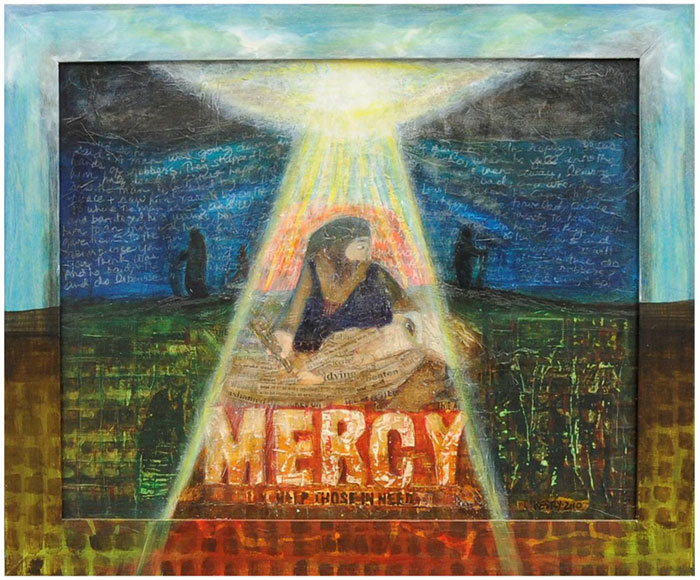

Scripture: Luke 10: 25-37 (with thanks to Clarence Jordan)

This is a heavy story. Well, the story itself isn’t that heavy. I mean, the man lying in the ditch regains his health thanks to the generosity of a Samaritan man–a fellow we call “the Good Samaritan.”

This is a heavy story because of all the baggage that comes with it. In terms of Jesus’ parables, it could be said that the Parable of the Good Samaritan is the most culturally recognizable of the parables.

Think about it. The phrase “good samaritan” has become a label for just about anyone who helps another in need. We’ve got Good Samaritan laws that offer legal protection to those who give reasonable assistance to those who are injured, ill, or in peril. Connecticut has one of those.

We have lots of charities that have been named in honor of this guy. One of the more well-known is Samaritan’s Purse founded, in part, by Franklin Graham, son of famed evangelist Billy Graham. It’s a organization that runs the world-wide program called Operation Christmas Child.

Suffice it to say that, when we hear the story of the Good Samaritan, we don’t just hear the story Jesus tells us. We also hear all the interpretations and implications that things like Good Samaritan laws and Samaritan’s purse bring with them.

So, I think it might be good for us to start at the beginning.

Now the first sentence of our gospel text this morning sets us up. We’re told by Luke that “Just then a lawyer stood up to test Jesus.” Now “lawyer” here could also be read as “scribe.” Scribes were, as you know, experts in the interpretation of the Torah, or the Law. We hear a lot from the scribes throughout the gospels, mostly from them trying to find whatever problems they could in Jesus’ teachings.

Here, the question is functioning in much a similar way: “Teacher, what must I do to inherit eternal life?” Surely aware of how loaded this particular question was, Jesus replies, in typical Jesus fashion, by asking another question, one that he knew the scribe would know the answer to. “What is written in the law? What do you read there?”

The scribe’s response is one that any good Jewish man would’ve been able to recite because the first part of it is part of what’s called the Shema, which is an affirmation of Judaism and a declaration of faith in one God. Good Jews are obligated to say Shema in the morning and at night. “You shall love the lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind; and your neighbor as yourself.”

Jesus seems satisfied with this answer, but the scribe, still trying to test Jesus (you can feel the tension starting to build) asks a second question: “And who is my neighbor?”

Well, isn’t that the million dollar question. Who is my neighbor? And so our story begins.

The story starts with a Jewish man traveling twenty miles or so from Jerusalem, high on a hill through the wilderness toward Jericho on the shores of the Dead Sea. It was a dangerous road; robberies were commonplace. And you know what happens. This man was indeed robbed who stole all his clothes, took his possessions, proceeded to beat him, then left him for dead.

Now before we actually meet this Good Samaritan, we meet two other characters, both Jews–a priest and a Levite. Levites were “highly esteemed Jewish religious figures associated with the temple in Jerusalem. One way to read this story is that these two men stand for everything right or correct in the faith. Now these two men were traveling the same road. And when they saw him, the moved to the other side of the road and went about their business.

Jesus doesn’t explain why these two men move to the other side. Some scholars argue that these two men, both prestigious religious and semi-political figures in the Jewish tradition of the time couldn’t touch a corpse. That would make them…unclean.

But Jesus’ story doesn’t offer any indication that was the case. Instead, what we’re told is that “when [they] came to the place and saw him, [they] passed by on the other side.” “Two people were unwilling to assume the risks that come with pausing in a dangerous place.”

And then our Samaritan arrives. Now in the greek text, the word translated as “Samaritan” shows up first. So it’s appearance would be a marked shift in the story. No, more than that. It would be a jolt. You’d be expecting another Jew, maybe not one carrying a prestigious title or role, to come strolling down this particular stretch of road, discover the man in the ditch and do the admirable thing and care for him.

But the next man coming down the road isn’t that Jew. It’s a Samaritan. Now, you know how sometimes there’s groups of people in town or say in church, who just don’t like one another. No one’s quite clear on what happened, on who said what. Lord knows it happened so long ago. But what they do know is that they don’t like each other. Well, the relationship between the Jews and the Samaritans is like that. Except, well, the know exactly why they don’t like each other. You see, they had a long history, but in the first decades of the first century, the Samaritans desecrated the Temple at Passover with human bones. This offense on behalf of the Samaritans, it would stand to reason, came out of a long hatred of the Jews. And the feeling is mutual.

So, when Jesus introduces this next character as a Samaritan, what he’s really doing is turning the story on end. You know how people bristle? You say something they might not agree with or they don’t like and the sort of shake it off. Jesus’ listeners bristled.

I bet they knew what was coming next. The Samaritan, moved with pity, bandages his wounds, puts the man on his own animal and took the Jew to an inn to take care of him. When he leaves the next day, he gives the innkeeper two denarii (we should read that as lots of money) and then promises to follow up with him when he comes back by.

I want to share with you another version of this story. Clarence Jordan was a greek scholar and civil rights activist from Georgia. He started Koinonia Farm in 1942 in rural, Southern Georgia in an effort to live in Christian community. It was an integrated community, long before that was socially acceptable. It was a community that was fire-bombed and continuously threatened during the height of the movement–all for living as friends with people who looked different. While you might not have heard of Koinonia, you almost certainly have heard of an organization that grew out of it: Habitat for Humanity.

Back to Jordan. Like I said, he was a Greek scholar–had his Ph.D. in Greek, and in an effort to make the gospels more accessible to the people he was living with he wrote The Cotton Patch Version of Luke and Acts.

Now here’s the way he tells this story:

One day a teacher of an adult Bible class got up and tested him with the question: “Doctor, what does one do to be saved?” Jesus replied, “What does the Bible say? How do you interpret it?” The teacher answered, “Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your physical strength and with all your mind; and love your neighbor as yourself.” “That is correct,” answered Jesus. “Make a habit of this and you’ll be saved.”

But the Sunday school teacher, trying to save face, asked, “But…er…but…just who is my neighbor?”

Then Jesus laid into him and said “A man was going from Atlanta [in North Georgia] to Albany [in South Georgia] and some gangsters held him up. When they had robbed him of his wallet and brand-new suit, they beat him up and drove off in his car, leaving him unconscious on the shoulder of the highway.

“Now it just os happened that a white preacher was going down that same highway. When he saw the fellow, he stepped on the gas and went scooting by (his homiletical mind probably made the following outline: 1. I do not know the man. 2. I do not wish to get involved in any court proceedings. 3. I don’t want to get blood on my new upholstering. 4. The man’s lack of proper clothing would embarrass me upon my arrival in town. 5. And finally, brethren, a minister must never be late for worship services.)

“Shortly afterwards a white Gospel song leader came down the road, and when he saw what had happened, he too stepped on the gas. (What his thoughts were we’ll never know, but as he whizzed past, he may be whistling, “Brighten the corner, where you are.”)

“Then a black man traveling that way came upon the fellow, and what he saw moved him to tears. HE stopped and bound up his wounds as best he could, drew some water from his water-jug to wipe away the blood and then laid him on the back seat. 0All the while his thoughts may have been along this line: “Somebody’s robbed you; yeah, I know about that, I been robbed, too. And they done beat you up bad; I know, I been beat up, too. And everybody just go right on by and leave you laying here hurting. Yeah, I know. They pass me by, too.”)

“He drove into Albany and took him to the hospital and said to the nurse “you all take good care of this white man I found on the highway. here’s the only two dollars I got, but you all keep account of what he owes, and if he can’t pay it, I’ll settle up with you when I make a pay-day.”

So that’s where we got up through both our version, but let’s keep listening to Jordan’s version:

“Now if you had been the man held up by the gangsters, which of these three–the white preacher, the white song leader, or the black man–would you consider to have been your neighbor?” The teacher of the adult Bible class said, “Why, of course, the nig–I mean, er…well, er…the one who treated me kindly.” Jesus said, “Well, then, you get going and start living like that!”

This is not a story about charity. it’s not a story about bandages and cleaning wounds and donkey rides and denarii. This is a story about our neighbor. What makes this such a compelling story is not that we can identify who would be the Levite and who be the Samaritan in our situation. It is compelling because in this story we could be any of the characters. It’s not a tale about the Levite or the Priest or the man who was beaten or even the Samaritan. This is a story about humanity, our humanity.

The thing that can make us uncomfortable about this story, the thing that should make us uncomfortable is that we, me and you, could be any character in this story at any time.

I think it’s easy to identify ourselves with the man on the side of the road. Life is hard–sometimes it’s really unfair. Sometimes you feel like you’ve been sucker-punched and left for the wolves. It’s also easy to feel the false sense of being a Good Samaritan. “Look at all the ways I help people; look at all the good I do.”

The unfortunate truth is that sometimes we’re the Levite. The one who, because it feels safer or easier or for whatever reason, cross to the other side of the road maintaining the distance between us and whoever strikes us as unclean.

But here’s the good news (the gospel of Jesus Christ always brings with it good news): there’s a question we can ask ourselves, and I mean really ask it. Who is my neighbor?

And then, when you ask it, genuinely look for the answer. Look in the hidden places, the unnerving places, the uncertain places. Look for the ones who don’t belong, the ones who don’t look like you, the ones just out to buy a pack of skittles.

And don’t make the assumption that people realize they are your neighbor. Help them to realize it through your actions, through how you love and care for them.

This is our call as a congregation, isn’t it? Jesus calls us to love people the best we can, to welcome them home and care for them. So, when it comes to caring for our people, our community, rather than ask how much is that gonna cost? Or, can we really make that work? Instead, let’s shift our focus and ask: Who is our neighbor? Then, we welcome them home. For in this house, we are all neighbors. And then, let’s be about God’s work of caring for them.

In the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost. Amen.

Get blog updates in your inbox!

Join my mailing list to receive the latest posts about creative visuals in worship, sermons, and more from revjonchapman.com.

You have Successfully Subscribed!